In our interactions, both personal and professional, it is common to misinterpret the actions of others. We often assume that hurtful or frustrating behaviors stem from ill intentions. Hanlon’s Razor challenges this instinctive reaction by offering a simpler and often more accurate perspective. This principle encourages us to avoid hastily attributing malice to others when a lack of knowledge, skill, or awareness could sufficiently explain their behavior.

At its core, Hanlon’s Razor invites us to pause before forming judgments and to explore whether mistakes and misunderstandings, rather than hostility, might be at the root of a situation. In doing so, it promotes healthier communication, greater empathy, and stronger relationships.

The Essence of Hanlon’s Razor

Hanlon’s Razor is succinctly captured by the statement:

“Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by incompetence or ignorance.”

In practical terms, this means questioning competence before intentions. When someone’s behavior appears harmful, it is often the result of oversight, lack of context, or miscommunication rather than deliberate ill will.

Consider a simple scenario: a team member consistently misses deadlines. It may feel natural to assume they are careless or even trying to undermine the project. However, upon closer examination, you may find that they have not received clear instructions, lack access to the right tools, or are overwhelmed by competing priorities. By viewing their behavior through the lens of Hanlon’s Razor, you open the door to constructive problem-solving rather than conflict.

Everyday Applications

Imagine sharing a living space with someone who leaves dirty dishes in the sink or makes noise late at night. The instinctive response might be to assume they are intentionally disrespecting you. However, they may simply be unaware of how disruptive their actions are or may not have developed habits around shared responsibilities. Without clear communication, frustration grows, but the true cause remains hidden.

In professional environments, similar misinterpretations occur. A manager who fails to respond to a message may not be dismissive but simply preoccupied with urgent matters. A colleague’s curt email might stem from stress rather than hostility. By applying Hanlon’s Razor, individuals can reduce unnecessary tension and foster a culture of trust and cooperation.

Why We Assume the Worst

The tendency to see malice where none exists has evolutionary roots. In ancient environments, assuming danger—whether real or imagined—was often a survival mechanism. Being overly cautious protected early humans from threats. Today, however, this instinct often works against us. In modern workplaces and communities, collaboration and mutual understanding are more important than defensive suspicion.

Moreover, cognitive biases such as the spotlight effect (the belief that others are paying more attention to us than they actually are) and the affect heuristic (making decisions based on emotions rather than logic) amplify misunderstandings. Recognizing these biases can help us apply Hanlon’s Razor more effectively and prevent small missteps from escalating into major conflicts.

Benefits of Applying Hanlon’s Razor

-

Conflict Reduction: By assuming error instead of ill will, we minimize unnecessary arguments and hostility.

-

Improved Communication: It encourages open conversations rather than silent resentment.

-

Stronger Relationships: In both professional teams and personal circles, trust grows when people feel understood rather than judged.

-

Better Decision-Making: Leaders and managers can focus on solving problems rather than assigning blame.

Limitations of the Principle

Hanlon’s Razor is not an absolute rule. Malicious intent does exist, though less frequently than our instincts suggest. The principle works best as a starting point for interpretation, not as a definitive conclusion.

It is generally safer to first assume error rather than hostility—especially in professional settings where collaboration is essential—but one must remain vigilant if patterns of behavior indicate otherwise.

Historical Context

The phrase “Hanlon’s Razor” was first introduced by Robert J. Hanlon in 1980 in a collection of sayings and aphorisms titled Murphy’s Law Book Two: More Reasons Why Things Go Wrong. While Hanlon popularized the phrase, the underlying concept is much older.

It is closely related to Occam’s Razor, a 14th-century philosophical principle that encourages selecting the simplest explanation with the fewest assumptions. In the same way Occam’s Razor guides logical reasoning, Hanlon’s Razor simplifies how we interpret others’ behavior. For example, if your manager does not reply to a message, the simpler explanation might be that they are busy, not that they are intentionally ignoring you.

Even centuries earlier, similar ideas appeared in literature and philosophy. The German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once observed that “misunderstandings and laziness perhaps produce more wrong in the world than deceit and malice.” This timeless insight underscores the universal relevance of Hanlon’s Razor.

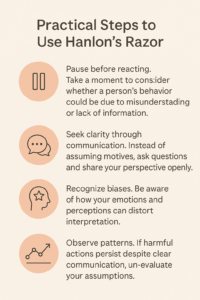

Practical Steps to Use Hanlon’s Razor

-

Pause before reacting. Take a moment to consider whether a person’s behavior could be due to misunderstanding or lack of information.

-

Seek clarity through communication. Instead of assuming motives, ask questions and share your perspective openly.

-

Recognize biases. Be aware of how your emotions and perceptions can distort interpretation.

-

Observe patterns. If harmful actions persist despite clear communication, re-evaluate your assumptions.

Final Thoughts

Hanlon’s Razor is a valuable framework for navigating the complexities of human interaction. By defaulting to simpler explanations, we can reduce conflict, improve teamwork, and build more resilient relationships. While not a universal truth, this principle reminds us that most mistakes are just that—mistakes, not attacks.

In a world where assumptions can quickly damage trust, practicing Hanlon’s Razor is not only an act of empathy but also a strategy for personal and professional success.