What is MVP and what’s NOT!

First, let’s understand what MVP is not because there are some misconceptions that a minimum viable product is the same as phase one of the project, the first beta, or something like that. This is not what a minimum viable product is. A minimum viable product is a minimal thing that you can do to test a value hypothesis and gain learning and understanding. You might say it is the cheapest thing you can do to prove a hypothesis. You can finish the first MVP, then get the results and move to the second one, and so on. The difference between these two is that the first one is all about delivery. What am I going to deliver? But the second one is all about learning. What can I learn? What can I learn from putting out this MVP and getting feedback and then maybe making the next one even better? So, it’s important that at the end of each MVP you decide whether to pivot or persevere. Should I pivot, that is, do something different or persevere, that is, continue doing what I’m doing?

MVP in practice

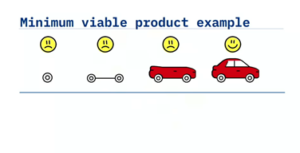

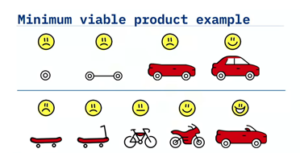

Let’s look at an example. Here’s a team that’s developing a minimum viable product for a customer that wants a red car. And so, in the first iteration, they deliver a wheel. The customer’s like, “What am I going to do with a wheel? I can’t do anything with this.” Well, we’re working iterations they say, we’re trying to be agile here. In the next iteration, we’ll give you something more.

And they give the customer a chassis. And the customer responds, “I still can’t do anything with this chassis.” And then, they give them a car with no steering wheel and then eventually they get the whole car. Now the customer gets this coupe. There was no feedback along the way. The team didn’t know until the end whether the customer was going to like what they built or not. The team did not understand how to create a minimum-viable product. They were just doing iterative development with no regard for whether each increment was useful or not. The second team understands the value of creating an MVP. At first, they give the customer a skateboard and the customer says, “What’s this? I asked you for a car and you’re giving me a skateboard.”

The team explains we’re testing the color. How do you like the color red? Is that the color you want? The customer says, “Oh yeah, red’s kind of cool but you know it’s really hard to steer.” The team says, “No worries.” In the next MVP, they give him a way to steer it. The customer says, “Well, okay, you did give me a way to steer it but I can’t go very fast. I need a better form of locomotion.” The team deals with that in the next MVP. In the next iteration, they give them pedals to go faster. Somewhere along the way, while riding on that motorcycle and feeling the wind in their hair the customer decides, “I really want a convertible!” In the first instance, the customer got exactly what they asked for months prior because the development team was just following a plan. But in the second instance, the customer got exactly what they desired because they were working iteratively and interactively with the development team. In the end, you develop something that’s a little bit different but it’s closer to what the customer really wants.

The ultimate purpose of MVPs.

Giving the customer what they really want is the main purpose of delivering an MVP. A minimal viable product is a tool for learning. It is an experiment to explore the value proposition with your customer. This experiment may fail and that’s okay because failure leads to understanding. What did you learn from that failure? What did it teach you? What is the next experiment? What will you do differently the next time? These are the questions that lead to gaining knowledge and understanding about what you are building. This is why we use MVPs.

Good luck with your next try at making an MVP..]